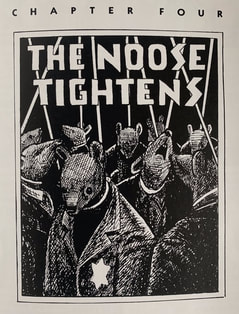

I’ve gotten on my soapbox about book banning before. I don’t often like to get on soapboxes, but as a writer, English professor, librarian, and all-around book nerd, it’s something that I am intensely passionate about. My students have to endure this every year when I force them to observe Banned Book Week. Fortunately, they’re largely receptive to the idea once they learn about it. They protest when they hear the books that are targeted, and write passionate defenses explaining why everyone should read their favorites. Sadly, this is not the case for everyone. Over the past several months, there has been a disturbing uptick in the removal or banning of books from school libraries and curriculum, not to mention determined efforts to silence the teaching of certain subjects. I won’t go into exhaustive detail of these various incidents here; NPR recently did an extensive report on the subject (well worth a read). Most of the book bans are along the lines that the American Library Association has extensively reported on for years. The most high-profile of these, however, came a little more than a week ago, when the school board of McMinn County, Tennessee voted to remove Maus from the eighth grade curriculum. The ruling has already garnered backlash and international attention, including a response from the author himself. If you’re not already familiar with the work (either prior to or as a result of this to-do), Maus is a graphic novel written and illustrated by Art Spiegelman. Published serially from 1980-1991, two collected volumes were released shortly thereafter. In addition to overwhelmingly positive responses from readers, Spiegelman’s work won numerous awards, including the Eisner for best graphic album and the Pulitzer Special Prize for letters. To date, it is the only graphic novel to have won a Pulitzer. Furthermore, Maus is considered by many critics to be among the most influential graphic novels of all time and–along with works like Watchmen, The Dark Knight Returns, and The Killing Joke–a major reason that graphic fiction is no longer considered a medium just for kids, and why in the decades since there has been a surge of critically acclaimed graphic fiction that goes far beyond the stereotypical superhero story. Of course, just because a work of literature is celebrated doesn’t mean that it’s appropriate for children. Up until this ban was implemented, the book was part of the district’s eighth-grade curriculum, and the board felt that the book was not appropriate for the age group. The school board provided their reasons for implementing this ban, citing “rough, objectionable language” (the minutes mention a total count of eight curse words) and the depiction of a nude woman. One board member additionally mentioned scenes of violence, including execution and suicide. On the surface, that certainly sounds extreme, but these objections seem less reasonable when considered in context. See, Maus is about the Holocaust. Specifically, it is the true story of Spiegelman’s father Vladek, a Holocaust survivor, in the years before, during, and after World War II. Spiegelman himself is a character in the frame story, which is set in 1978 as he slowly convinces his father to tell his tale. The art is simple and cartoonish, entirely in black and white, and uses anthropomorphic animals to represent the various groups involved in the war. Spiegelman, his father, and the other Jews (whether European or American) are mice, the Nazis are cats, Americans are dogs, Poles are pigs, French are frogs (excluding Spiegelman’s wife, a French woman who converted to Judaism for marriage), Swedes are reindeer, British are fish, and Gypsies are moths. Despite this, the story is powerful and personal, perhaps more so because the reader is not expecting it from the presentation. Despite Vladek’s flaws (which Spiegelman does not shy away from), the reader connects with and deeply empathizes with him and the other mice as they are persecuted, imprisoned, and yes, even executed. Children learn about the Holocaust in school. It’s not uncommon for them to read Anne Frank’s diary in middle school (I did, in 7th grade, and three years later Night was part of the curriculum). Lessons focus on the events of World War II and, while the gorier details are usually omitted in the younger grades, the Holocaust is mentioned. It has to be. And especially because there are fewer and fewer survivors and witnesses to the Second World War left each year, it is becoming increasingly rare for younger generations to feel a personal connection to those events. My grandfather (a WWII paratrooper) never talked about his experiences with me, but I was acutely aware that he was there, that these horrors were in living memory, and that made it feel more real and alive than other events that I learned about in history class. We can teach children about history all we want; we can drill dates and names and statistics into their heads and make them memorize them, but it’s difficult to connect with numbers and figures. You can tell someone that an estimated six million Jews died in the Holocaust, not to mention the millions of non-Jews, but the sad reality is that a figure like that is difficult to wrap one’s head around. We can understand in the abstract that people were arrested, imprisoned, tortured, and murdered in massive quantities, but it would break us to connect genuinely with the suffering of each individual victim. It is for this reason that literature about this time is so important. The first-person narration of someone who lived it, who watched as their rights were ripped away from them and they were treated like vermin, touches us in a way that no amount of facts and figures can. Even in Maus, Vladek protests that his son is including details that have “nothing to do with Hitler, with the Holocaust.” Art responds that he’s including them because “it makes everything more real–more human.” I’ve long forgotten most of the details that I was taught in history class about World War II, but the images that I read in Elie Weisel’s Night in my tenth grade English class are burned into my brain. Those 120 pages and the pain, longing, and despair they inspired will be with me for the rest of my life, and I’m glad of that. The Holocaust was one of the darkest moments in human history. But we can’t look away from that darkness. There’s a reason so many Holocaust memorial efforts (including the one from the German government) use the slogan of “Never Forget.” Looking at the brutality, understanding why it happened and who it happened to, helps us not only understand it, but to learn from it and ensure that it never happens again. Naturally, all of this is reasonable in principle, but the question remains: how much of this do we expose children to? This is the question that plagues so many of these controversies, and is often at the heart of challenges made to the ALA in the first place. Many of the challenges made to books are done so on the basis of protecting children from inappropriate content: violence, drug use, sexual content, racism, etc. Those who call for bans claim that they’re doing so for the greater good, that children are too impressionable to be seeing or reading about these things. The question, then, is when can they learn about these topics? Is it going to be upsetting for some students to see and read about the events of the Holocaust? Of course it is. The events are upsetting. But they are going to have to learn about these events sooner or later, and literature is the best avenue for teaching them. In her essay on trigger warnings, English educator Siobhan Crowley argues that excluding material from the curriculum because it contains potentially upsetting content amounts to “criminal neglect.” The list of literary works that engage with upsetting or problematic content is extensive, often because authors deliberately set out to discuss exactly these issues. “Great literature is great,” Crowley declares, “because it tackles these painful topics.” Literature offers us an avenue into these events and a chance to connect and identify with people who experienced some of the most impactful moments of history, and the teaching of literature provides young people with a space to engage with and discuss the issues connected to those events. Coddling students does them no favors. They will become aware of these issues regardless. Classrooms should be safe havens; these topics shouldn’t be drilled into their heads without context and discussion, and the perception that this is what happens is woefully misguided. No teacher would simply force their students to read Maus and declare “there you go. Holocaust bad.” That’s not teaching. Teaching is discussing and analyzing and providing students an opportunity to voice their thoughts and reactions. And yes, that includes moments that might be confusing or scary, but a classroom is the place to tackle those moments safely. The detriment that comes from depriving students of a mature and thoughtful discussion of these “upsetting” materials becomes even more apparent when you consider that these bans simply don’t work. Students are still reading the content. If anything, banning a book only makes it more attractive. Sales of Maus are up more than 700% in the wake of the McMinn County ban, and vendors are offering to send the book to impacted students for free. Students will access these materials regardless. Even if you disagree with the content, you should acknowledge the value in allowing young people to discuss the content openly and without fear of reprisal. It’s how we ensure that they truly understand the material, and learn the lessons that literature is intended to teach.

0 Comments

I grew up with Dr. Seuss, as did most people. My parents grew up with him, and have remained massive fans to this day. My mom, a former elementary reading specialist, adores The Lorax, and every year on March 2nd would enthusiastically don a Cat in the Hat hat for Read Across America Day. Not a holiday season goes by without my dad (a retired English teacher and principal) watching and singing along with "How the Grinch Stole Christmas.” The animated 1966 Boris Karloff one is the definitive version, he insists, and I agree. My parents read his books to my sister and me until we could read them ourselves; they now read them to their grandchildren, and can probably each recite several of his books from memory. Seuss is a cornerstone of my childhood. So, of course, it was a shock to hear the recent news about his work. For those who aren’t aware, Seuss Enterprises--the organization that manages the late writer’s estate and oversees the continued publishing of his works--announced on the late author’s birthday that they would cease production of several of Dr. Seuss’s books. The announcement sparked immediate controversy, with many crying that Dr. Seuss was being “cancelled,” i.e. scrubbed from the collective cultural consciousness. If Dr. Seuss is being erased, what’s next? Is nothing sacred? As many news outlets have pointed out, and as Seuss Enterprises explained in their statement on the matter, the decision was reached after lengthy consideration and discussion with a panel of experts. The books in question “depict people in ways that are hurtful and wrong,” per the statement. But before you start clutching your beloved copy of The Cat in the Hat to your breast and swearing they’ll pry it from your cold, dead hands, you should know that this decision affects only six books: And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street, If I Ran the Zoo, McElligot’s Pool, On Beyond Zebra!, Scrambled Eggs Super!, and The Cat’s Quizzer. Oh, never mind then. Crisis averted. Personally, I wasn’t aware that the last four of those books even existed, and I’m willing to bet that many people outraged over the news didn’t either. They’re not exactly popular. As reported by the NYT, Bookscan, which tracks the sales of physical books at a number of retailers, reports that McEligot’s Pool and The Cat’s Quizzer haven’t sold a single copy in years. And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street sold just 5,000 copies last year. To put that in perspective, Green Eggs and Ham sold 338,000, and the ever-popular graduation gift Oh, the Places You’ll Go! sold over 518,000. Of those books impacted, If I Ran the Zoo is probably the most well-known, but the fact that the book contains racist imagery shouldn’t be news to anyone who’s been paying attention. Controversy has hounded that book since at least 1988. Someone like Dr. Seuss is a nigh-sacred figure. Think of all the joy that his work has brought to millions around the world. To learn that he was guilty of perpetuating racist caricatures is shocking, especially contrasted with the wholesome messages of much of his other work. Indeed, several of his works have a decidedly antiracist tone. For some, this is confusing. How can Seuss be at once racist and not racist? And if he’s not racist, can we keep his work around? As children’s book scholar Philip Nel points out in a phenomenal interview with Slate, people “see racism as an either/or—like, you’re on Team Racism or you’re not. But you can do anti-racist work and also reproduce racist ideas in your work.” Commenting on the same issue to the New York Times, Nel thinks this reevaluation of Seuss’s legacy is a good thing: “There are parts of his legacy one should honor, and parts of his legacy that one should not.” This touches on a larger issue: our dislike of nuance. When we’re faced with the reality that a person we admire has done terrible things (the figures implicated in #MeToo, for instance, or the fact that many of the Founding Fathers owned slaves), or that something we like has problematic elements (the Seuss works in question, or Dungeons & Dragons), we sometimes have a difficult time reckoning with that. We ask ourselves: can I continue to enjoy the good, now that I know about the bad? and the answer that we reach determines how we proceed. For some, the solution is to carry on like nothing has changed. It keeps the image pristine and perfect, and does not require us to reevaluate decades of good memories. For others, the knowledge taints the entire experience, and we want nothing to do with it any longer. To continue to enjoy the work elicits feelings of guilt and even complicity. Those people in the second group often enrage the people in the first, who accuse the latter of “cancelling” things, or trying to ruin it for everyone. Sometimes, those cries are accurate, but most of the time they’re just reactionary melodrama. For a third group, admittedly the minority, caveats are introduced. Nel’s quote about Dr. Seuss can be applied to many of the things that we hold dear. There are parts of any legacy that we should honor, and parts that we should not. Does fantasy have racist origins? Yes, but it has also been used to give a voice to the voiceless, to offer consolation to the forlorn and grieving, and to critique the problems in our own world. Is Joss Whedon toxic and emotionally abusive? Yes, but “Buffy” is still a groundbreaking work of feminist television, the product of many hands and minds. Did the Founding Fathers own slaves? Yes, but they also helped build the foundation of a great nation, and every day we strive to make it more in line with their noble vision. We can celebrate the good work these people did while still acknowledging that they were (sometimes deeply or even irredeemably) flawed individuals. There’s a school of literary analysis called Death of the Author, which states that a work speaks for itself, regardless of the author’s intentions or anything the author ever said about the work or did in their personal lives. The logic is that once a work goes out into the world, it doesn’t belong to the creator anymore. It belongs to the public, and how they interpret it and what they do with it is their own. I’ve always been a proponent of this school of thought, and I think it’s one that we can apply more broadly. People do great things, and they often fail to live up to the ideals present in the great things they do. That doesn’t detract from the greatness of their acts, or invalidate the even greater things their work might have inspired. It just means we have to change our focus from who they were to what they did. Thomas Jefferson himself said that “As [mankind] becomes more developed, more enlightened, as new discoveries are made, new truths disclosed, and manners and opinions change with the change of circumstances, institutions must advance also, and keep pace with the times. We might as well require a man to wear still the coat which fitted him when a boy, as civilized society to remain ever under the regimen of their barbarous ancestors." These words are inscribed on the Jefferson Memorial, and I think we need to take them to heart. If our ancestors look barbarous, that’s not an indictment of them. It’s a testament to us, how far we’ve progressed, and what we’ve learned. We can be at once upset with what they did and celebrate what we’ve learned from it. The two don’t have to be mutually exclusive. It just means we have to take the bad with the good. We can’t pretend history is perfect, but we can’t afford to throw everything out, either. Dr. Seuss’s works will continue to bring joy to millions more for decades to come. The decision to cease printing of these six books--six books that, apparently, nobody was reading anyway--is not a loss to our culture, and not an erasure of our past. Those works remain in collections around the world, where they will doubtless be preserved and studied and discussed in the proper context. Seuss Enterprises, charged with maintaining Dr. Seuss’s legacy, has simply decided that the depictions in these works do not reflect the larger philosophy of the man we all hold dear. We’re continuing to honor the parts that are worth honoring. As a great man once wrote: “Unless someone like you cares a whole awful lot, Nothing is going to get better. It's not." ~NG  Recently, the library I work at posted an interesting article to its social media: a piece from Wired entitled “D&D Must Grapple With the Racism in Fantasy.” This article sparked some discussion among students as well as staff, including a lengthy conversation with one of my fellow librarians. As a writer and avid reader of fantasy, as well as a D&D player, I realized that I had a lot of thoughts on the issue, and especially with the way that the Wired article addresses them. First and foremost, it’s irresponsible to ignore the racist and sexist underpinnings of fantasy. That’s not to say that fantasy as a genre is racist and sexist--far from it; there are numerous authors who use fantasy as a way to comment on, escape, or even reject the prejudices that permeate the real world. It’s in the origins of fantasy that we find some troubling ideas. J.R.R. Tolkien, considered by many to be the father of modern fantasy, wrote extensively on the inspirations behind the races of Middle Earth, and scholars have spent decades dissecting his work. Many scholars agree that there are problematic racial stereotypes within The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. This is most notable in the way that Tolkien characterizes certain races of his world, particularly the Orcs. In a letter, Tolkien admitted that Orcs were meant to represent “degraded and repulsive versions of the (to Europeans) least lovely Mongol-types.” This reflects what John Magoun called a “moral geography” in Middle Earth: the west (which includes the Shire, Gondor, Rohan, etc.) is civilized, while the east (realms like Mordor, Harad, and Rhun) is barbaric. The parallels between this and the imperialist ideas of Tolkien’s day should be obvious. Even the more heroic races of Middle Earth are not without their associations. In the years following the publication of The Hobbit, Tolkien was clear about the parallels between his Dwarves and the Jews, even stating that the Dwarvish language is Semitic in construction. He and others have drawn additional parallels, though there is some debate as to whether these parallels are meant to dispel antisemitic stereotypes or reinforce them. Matt Lebovic of the Times of Israel sees the parallel as largely heroic, and a rewrite of the antisemitic themes found in Wagner’s Ring Cycle. Scholars like Renée Vink, writing for the journal Tolkien Studies, find the portrayal largely negative, citing in particular the creation myth for the Dwarves and its parallel to Christian ideas toward Jews at the time of Tolkien’s writing. I could go on, but the focus of this discussion is meant to be on Dungeons & Dragons. Suffice it to say that Tolkien’s mythology, though wonderful and foundational for the genre, has its racist underpinnings, and those threads have endured, whether intentionally or unintentionally, in the decades that have followed. The publishers of D&D, Wizards of the Coast, have acknowledged their perpetuation of some of these stereotypes, and are constantly working to improve their product to be more sensitive and inclusive. The question here, then, is not if the works that inspired D&D are racist, but if D&D perpetuates these problematic ideas. The short answer to this is yes, but the longer answer is that doesn’t necessarily have to. My issue with the Wired article linked above is how it addresses this caveat. One of the article's main points of contention is with the racial bonuses built into the game’s rules. For the edification of non-players: all player characters, nonplayer characters (NPCs), and monsters within the D&D universe have six ability scores--strength, dexterity, constitution, intelligence, wisdom, and charisma--that impact their skills and dice rolls made with regard to those skills. These scores can range from 1 (abysmal) to 20 (exceptional), with the average being 10. For reference, a commoner (which is used as the basis for most human NPCs players encounter) has scores of 10 in every category. This establishes 10 as the baseline. Though the numbers offer a quantitative expression of these abilities, the baseline of 10 shows that these abilities are relative. A cat, for example, has an intelligence of 3 (much lower than that of the average human) but a dexterity of 15 (much greater than the average human). While players get the freedom to determine their own ability scores when creating a character (there are several methods for doing this fairly; each DM has their own preference), these scores are supplemented by racial bonuses, modifiers applied to ability scores based on the player’s chosen race for their character. Humans, being versatile, get a +1 to every ability. Elves, being quicker and more agile, get +2 to their dexterity score. Half-Orcs get a +2 to their strength and a +1 to constitution. Each race has their own unique benefits, but none of the 43 playable races in the current rules receive a penalty to any ability. The article describes these bonuses as “lore-sanctioned stereotyping,” but based on the way that NPCs and monsters use the same ability scores, I would argue that it’s less a matter of stereotyping and more a matter of physiology/biology. By incorporating racial bonuses, it seems to me that the game isn’t so much saying “all orcs are strong,” but rather “based on biology, orcs tend, on average, to be stronger than other sentient humanoids.” It’s easy, given both the language that the game uses and the fact that our real world has only a single sentient humanoid species (humans), to equate its use of “race” with our own. It would be more accurate to think of the races of D&D as “species.” Elves, Dwarves, Orcs, etc. are all sentient humanoid species, but on a biological level, they are different from humans. They have different physiologies. It’s not a stereotype to say that a cheetah is faster than a human, or a gorilla is stronger, or a polar bear is tougher. It’s a relative comparison, and we should think of D&D’s races the same way. The other aspect of this that the article minimizes is player agency. The article argues that racial bonuses push players toward certain class and race combinations. And yes, there is definite temptation for players to pair their choice of race with a class that will benefit from those bonuses. Because of their bonuses to strength and constitution, and their lore-based propensity toward violence and savagery, the article points out that orcs make excellent Barbarians. This is true. As a martial class, Barbarians benefit from having high strength and constitution. However, Fighter and Paladin are also martial classes, and also perform better with high strength and constitution scores, and while this is an aspect shared by all three classes, each of these three have wildly different abilities and roleplaying recommendations. A Barbarian is a savage fighter, like the Viking berserker, who fights with wild abandon. By contrast, a Paladin is a disciplined champion of their chosen god, sworn to fight for ideals like truth, justice, and freedom. The racial bonuses of an orc are suited for both, but the playstyles of each class are vastly different. But though the higher strength and constitution of Orcs and Half-Orcs are naturally suited for a martial class, there’s absolutely nothing in the rules that prevents any race from playing any class. The player has the final say in the matter, not only in which race and class they choose, but also where they choose to put their ability scores. They can choose to play into the strengths of the chosen race or reject them, based on their choice of class, character background, alignment, and (perhaps most importantly) the decisions they make as they level up and progress through their adventure. A good analogy for this is the nature vs. nurture debate. We are all products of our biology; there are inborn traits that we all have that we can’t help, but we change and develop based on what we’re exposed to as we grow. Player decisions are the nurture to the nature of racial bonuses. While some players might find it limiting that certain races are predisposed toward certain classes, many players enjoy the challenge, and constantly find new ways to innovate and craft unique, engaging characters. The latest supplement for the 5th Edition, Tasha’s Cauldron of Everything, does something to alleviate these limitations. It provides a new way of allocating racial bonuses, allowing the players to shift things around to better suit their character’s class or background. It also paves the way for players to create their own variants on existing races or entirely new races--a process that always existed in an unofficial capacity (known as “homebrew”), but was only permitted by certain DMs in certain circumstances, and usually was difficult to balance properly in the game’s mechanics. TCE resolves this, providing an easy path for balanced homebrew. Wired quotes blogger Graeme Barber, who calls these “minor, superficial changes” and derides the supplement by reminding his readers that “optional rules are optional.” This last statement in particular struck me as odd, because any person could use that same logic to dismiss practically any rule in the Dungeons & Dragons handbook. One of the perennial allures of the game is its freedom and adaptability. The rules exist as written to help facilitate and balance the game, but they are intended to serve primarily as guidelines. In the preface to the Player’s Handbook, the backbone text of the Edition, co-lead of the project Mike Mearls writes that “D&D is your personal center of the universe, a place where you have free reign to do as you wish.” This is reinforced in the Dungeon Master’s Guide, which openly declares that “the DM interprets the rules and decides when to abide by them and when to change them.” Yes, the rules provided in supplements are optional, but by the admission of Wizards of the Coast, so are all of the others. For Barber to dismiss TCE simply because he feels it doesn’t go far enough is a bit silly. The rules are not the be-all-end-all. They are merely a basis. By the very parameters of the game, he is free to ignore or expand upon them as he and his DM please. At the end of the day, Dungeons & Dragons is an evolving game. The rules provide a foundation for play, but the players and the DM have the freedom and the authority to do what they wish with that foundation. It’s important to acknowledge and reckon with the problematic elements of D&D’s inspirations, but to assume that players will fail to see these issues, or willingly reinforce them, is extremely shortsighted. In the PHB preface, Mearls writes, “The first characters and adventures you create will probably be a collection of cliches. [...] Accept this reality and move on to create the second character or adventure, which will be better, and then the third, which will be better still.” We all have preconceived notions of fantasy, and these notions are the basis for much of Dungeons & Dragons, and as a result many players might find themselves reinforcing them when they first sit down to a table. My first character was a Dwarf Cleric, which would be considered an optimal race and class pairing. Most players I know started with a similarly ideal pairing, simply because they approach D&D the same way they approach every other game: with strategy and an aim to win. But D&D is not like other games. The object is to play. Whether you complete the adventure or die horrifically along the way, you succeed as long as you enjoy the experience. As Mearls says, this is something that most players don’t realize until they play, and once they come to this realization, they begin to formulate new characters, and new ways to approach the game, and these are often wild and strange and totally at odds with notions of “optimization.” One of my favorite anecdotes from the D&D world is one that I’ve seen circulating online. Players and DMs trade stories constantly, and as a result are constantly inspiring one another to innovation. This story concerns a player who chose to create a Half-Orc Rogue. Rogues are thieves and assassins, masters of stealth and subterfuge. Half-Orcs gain no innate bonus to dexterity (a rogue’s primary ability). This player made his character enormous, and put absolutely no points into stealth. What he did, however, was capitalize on the fact that Half-Orcs have innate proficiency in the intimidation skill, and bulked up his proficiency there. Whenever he was caught trying to sneak somewhere (which happened frequently), he would shout “YOU DO NOT SEE ME” in an attempt to intimidate NPCs into compliance. Because of his high skill, these efforts usually worked. By the standards of the game, this would not be considered optimal or traditional, but I’m sure that the player and his party enjoyed every second of it, and that’s what matters. This conversation is an important one to have. We should all--players, DMs, and non players alike--be aware of the problematic origins of these high fantasy elements. That awareness can help encourage us to break free of the tropes, and create new, imaginative characters that subvert and twist or openly reject these tropes. Orcs in Middle-Earth may have been intended as metaphors for the “Yellow Peril” when Tolkien wrote them, but the beauty of metaphors is that they are polyvalent. Which brings me to my final point, and, fittingly, one that draws heavily from Tolkien. The fundamental purpose of fantasy, as Tolkien himself often asserted, was escapism, a temporary consolation from the ills of the real world. This is true of games like D&D, which not only offer the traditional escapist benefits of all fantasy, but also, through player agency, provide an exercise in wish fulfillment and power fantasy. Players can be whoever and whatever they wish. They can be stronger, wiser, more agile; they can hurl powerful spells, transform into beasts, and perform feats of superhuman prowess. In D&D, we can try out a different identity just for a little while, or even play as an ideal version of ourselves. Is it any wonder that D&D has such a devoted following in the LGBT community? Tolkien and those who came after him may have intended their creatures to mean one thing or another, but once those creatures are sent out into the world, they cease to belong to their authors and instead belong to us. Virginia Woolf said that the only advice we can give each other on reading “is to take no advice, to follow your own instincts, to use your own reason, to come to your own conclusions. [...] To admit authorities, however heavily furred and gowned, into our libraries and let them tell us how to read, what to read, what value to place upon what we read, is to destroy the spirit of freedom which is the breath of those sanctuaries. Everywhere else we may be bound by laws and conventions--there we have none.” D&D, I would argue, could be added to that. We enter a world of our own creation when we play. Though we use the words and inventions of others (whether of Tolkien, Wizards of the Coast, or some ancient mythology), what we do with those inventions is our own. The DM is the only authority--to admit any other would destroy the illusion. These creatures are ours, and they can mean whatever we want them to mean. As Freud might have said (if he played D&D): sometimes, an Orc is just an Orc. ~NG  My girlfriend and I have been living together for about a year and a half now. While this is not my first relationship, it’s my first (and hopefully only) experience cohabitating with a romantic partner. One of the unexpected aspects of this new lifestyle has been the establishment of traditions as we both meld our respective ones together and adopt new ones. This year, for instance, I have a Christmas tree for the first time ever. Last year, we started observing a new tradition. We can’t claim credit for it; it’s a longstanding tradition out of Iceland known as the Jólabókaflóðið, or Christmas Book Flood. The custom has its roots in World War II, when import restrictions and low paper prices led to the country releasing all of its new books just once a year: during the week before Christmas. This has, predictably, led to books being a popular Christmas gift. The current iteration of the tradition has people exchanging books on Christmas Eve, and then spending the evening curled up with those new books. Our respective families have numerous traditions and gatherings throughout the Christmas week, but Christmas Eve (thus far) has been left to us. Last year, we spent the evening observing Jólabókaflóðið (based on my research, this is pronounced yo-la-boak-a-fload). After dinner, we made a batch of hot buttered rum and settled in with our new books. I got her Sarah Perry’s Melmoth, a gothic mystery story, and she got me Philip Pullman’s retellings of Brothers Grimm Fairy Tales. I made significantly more progress in mine than she did, mostly because I kept interrupting her to share with her how brilliantly Pullman had respun the classic tales. It was a lovely, cozy evening, and I’m very much looking forward to doing it again tonight. I can’t say what I’ll be giving her for the Book Flood this year; she does read these, after all. The Christmas season can be crazy; we both come from close-knit families, so there’s always a bunch of gatherings crammed into a relatively small time frame. Last year, we went to five different Christmases throughout the day. I don’t mean this to sound like a complaint; I love both or our families and always enjoy spending time with them, but amid the constant gatherings and traveling between the gatherings, the day tends to go by in a blur. It’s nice to have the contrast of the night before, which is slow and relaxed and quiet. Of course, with the pandemic still raging on, things will look very different this year. Nonetheless, we’re still having our quiet night of reading on the 24th. At this point, it’s probably short notice to adapt your own traditions to include this, but if this sounds like something you’d enjoy, consider it for next year. Happy holidays to you all! Enjoy the season, and here’s to a brighter new year!  I avoid talking about politics. Politics is a volatile and toxic topic of discussion; this is something I realized when I was 18 and registered to vote. Not liking the rigidity I found on either side, I registered as an Independent. I’ve used that label to duck political discussions in the past, and avoid people canvassing for various parties. But given everything that’s been happening lately, I can’t keep my mouth shut. Well, perhaps I could if I tried harder, but I don’t want to. The final straw in all this came this morning, when I read the White House Press Secretary’s response to questions regarding the now-infamous incident in Lafayette Square on Monday night. If you missed it, she denied everything and claimed that the event that we have extensive video and physical evidence of (and which, if you listen, can be heard happening in the background during Trump’s speech in the Rose Garden that same evening) didn’t happen the way it did. It just didn’t. I would call this idiotic and insane, but those don’t seem strong enough descriptors. In putting forth this blatant denial, they expect us to disregard any narrative contradictory to their own, and accept their narrative without question or hesitation. If you’re having flashbacks to reading Nineteen Eighty-Four in high school, I don’t blame you, because this is a major plot beat of Orwell’s novel. The totalitarian Party controls information, and tells its citizens what to think, and the citizens are meant to ignore any evidence they have that contradicts the Party dogma. And if that comparison scares you or makes you uncomfortable: good. It should. What is happening right now is terrifying; I won’t pretend that it’s not. But the protests and the riots and the militarized tactics responding to it are the culmination of decades of systemic oppression so woven into the fabric of the nation that many of us can go through our lives entirely ignorant of their existence. If you are one of those people, take a moment and consider how fortunate you are, and remember that simply because something does not personally impact you doesn’t mean that it does not exist. I won’t go into exhaustive details; better people than myself have documented this extensively. What I will do, however briefly, is remind everyone reading this of the foundational text of this nation, which reads: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” There is overwhelming evidence that a massive portion of our population is being denied these fundamental rights, and as a result are not being held as equal. Regardless of your party or ideology, that should make you pause. We’re not living up to the basic tenet of our nation. Clearly, something needs to change. I stand wholeheartedly with the tens of thousands of brave people out there protesting. I am, however, a coward, and given the fact that we’re in the midst of a global pandemic, I’m wary of being around any more than three people at any given moment. Still, I commend those marching, and without hesitation label them far, far more courageous than myself. If you’re like me, and are hesitant to go out and participate physically, good news: there are still things you can do. I’ve donated both to the ACLU and the NAACP (small donations, admittedly, because I’m far from wealthy, but donations nonetheless), and there are dozens of other organizations out there doing good in the midst of all this awfulness. Consider lending them a hand. Even a small one makes a difference. If you think this whole rant is too political, fine. Be angry with me. Yell at me on Facebook, or in the comments here. Vow to stop reading my posts. I don’t care. There are more important things going on than feelings too fragile to hold up to the barest scrutiny. If you can, with good conscience, sit back and allow these egregious violations of our fundamental liberties to continue, and still call yourself an American, then...well, we strongly disagree on what that term means. One of my favorite texts to give my students is Frederick Douglass’s speech, “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July.” I use it in both my composition course and my public speaking course. You can find the full text here, or a beautifully performed abridged version by James Earl Jones here. One of my favorite moments from the speech is the paragraph below, which I feel applies powerfully to our current situation: “At a time like this, scorching irony, not convincing argument, is needed. O! had I the ability, and could I reach the nation’s ear, I would, to-day, pour out a fiery stream of biting ridicule, blasting reproach, withering sarcasm, and stern rebuke. For it is not light that is needed, but fire; it is not the gentle shower, but thunder. We need the storm, the whirlwind, and the earthquake. The feeling of the nation must be quickened; the conscience of the nation must be roused; the propriety of the nation must be startled; the hypocrisy of the nation must be exposed; and its crimes against God and man must be proclaimed and denounced.” That speech was given in 1852, as a call for an end to slavery. One hundred and sixty-eight years later, it’s time for another storm, another whirlwind, and another earthquake. That’s what we’re seeing. It’s powerful, and scary, but I firmly believe that good will come of this. If you can’t or won’t stand physically with those on the streets for whatever reason, I encourage you to do something. Donate. Protest. Contact your representatives. Something needs to change, and the more voices in that chorus, the sooner it’ll happen. ~NG  Philippe de la Muerte / CC BY-SA (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) Philippe de la Muerte / CC BY-SA (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) The other night--as we’ve done many times over the last several weeks--my girlfriend and I decided to watch a movie. We have lists of our favorite films, and have made notes of which films the other hasn’t seen, with the plan of introducing them to each other. The night in question, we picked one from my list: John Carpenter’s seminal 1982 horror film, The Thing. As we watched the movie, it occurred to us that the major plot beats and themes of The Thing seemed oddly appropriate in this time of social distancing and self-quarantine. So allow me to get slightly more academic than I normally do in these posts, and examine the elements of the film a little more closely. Horror, at least good horror, is known for relying heavily on metaphor to explore and comment on prevalent social fears. Horror allows us to give a face to faceless dread, and offers some consolation by showing us that we can fight against it. For The Thing, that faceless dread is the invisible invader, the predator that we can’t see until it’s too late. Despite being almost forty years old, The Thing is the perfect film for a pandemic such as this one. Major spoilers for The Thing follow, so if you’re unfamiliar, or don’t wish to ruin it for yourself, feel free to stop here. I won’t take it personally. I won’t even notice. The film is set at an American research station in Antarctica. A few scenes in the film take place outdoors, but most of the action is inside, set against plain white walls with few or no windows. There is repeated conversation regarding the weather and temperature outside, which makes the message clear: they’re not going anywhere. Like those of us working remotely or otherwise staying at home, this feels all too familiar. It’s bad out there. We don’t go out unless we have to. Early in the film, we see that tensions exist between these men, and these tensions grow and bubble over as the stakes get higher. Where once we might have chided the characters for being short with one another, now it feels relatable. It’s what happens in prolonged isolation. Trapped in a confined space, we can get tense and irritable. But Nick, you say, The Thing is hardly unique there. Isolation is a common theme in horror: The Shining, Alien, Evil Dead...the list goes on. It’s true; being cut off is something of a trope in horror, and it’s understandable. It’s a common fear that’s easy to play into. But the similarities don’t end there. The titular Thing in the film is a shapeshifting alien, accidentally awoken from the ice by Norwegian scientists. The Thing devours every living thing in its path, absorbing them so completely that it can then perfectly replicate their bodies, down to the cellular level. The monster can even mimic speech patterns and mannerisms, making it almost undetectable. As a result, a major element of the film is suspicion: when your enemy can look and act exactly like the people you know and trust, you have to suspect everyone. It doesn’t take long for the characters to turn on each other, and assume that everyone else is “one of them.” They threaten each other, cast doubt on one another, and make repeated insistence on their own humanity. It’s this suspicion that really drove it home for me. We’re dealing with a virus that’s easily transmitted, and even though we’ve all read horror stories of the symptoms of the disease, we can’t rely on that alone. Experts have been saying for months that a large portion of people with the Coronavirus are asymptomatic. I’ve seen estimates as high as 75%. That means that for every person showing symptoms, there’s as many as three who aren't. With every interaction that we have with other people, we have to assume that they have it and we don’t. In this regard, we’re not dissimilar from MacReady (played by Kurt Russell), who ties up his comrades and threatens them with a flamethrower as he tries to determine whether or not they’re still human. Ours goes a bit deeper, however, because we also have to assume that we do have it, and take precautions against spreading it to others who don’t. And, like MacReady and company, we’ve been quick to turn on each other. We criticize people who we don’t feel are taking the appropriate precautions. We know we’re human--it’s those other idiots we’re not so sure about. Hell, Blair (Wilford Brimley) is even forced into quarantine when the others fear that he might no longer be himself. The whole thing comes to an explosive climax when MacReady faces off against the creature in the tunnels beneath the station, using all the dynamite he can find in a last-ditch attempt to eradicate the Thing. He’s accepted that he’s not making it out, but he wants to make sure that it doesn’t, either. Even this is in line with one of the messages that I’ve been hearing over the last several weeks: our priority should be stopping the spread. If we have it, we have it, and all we can do is prevent it from spreading to others. Sitting inside as much as we can and wearing a face mask when we go out is less dramatic than what MacReady does, but it is meant to be metaphor, after all. The film ends with MacReady and Childs (Keith David) sitting near the smoldering remains of the research station. They’ve been out of each other’s sight, and MacReady has even been out of ours for a few minutes. Neither can confirm if the other is still human, so they sit in the snow and share a drink. In this last moment, they’ve realized that their suspicion is pointless. They’re stuck in the Antarctic. If both of them are human, neither of them is going anywhere, and if the other is the alien, the human is powerless to do anything about it. It’s not a happy ending, I realize, but it is a cautionary one. The film’s bleak ending is a result of missteps made throughout its plot. The characters didn’t realize what they were dealing with until it was already among them, and even then, despite their best efforts, it overcame them. Like them, we downplayed our current situation until it was too late. Where we can differ from them, however, is where we go from here. Keep hunkering down, friends. I know it's frustrating to sit inside so much, but little by little, we're getting there. There’s light at the end of this ordeal, and--at least as of right now--I’m optimistic that it’s not coming from a burning research station. ~NG  I’ve been thinking long and hard about what to write for this entry. I knew I was going to write one, but how I would go about it was somewhat of a mystery. There are so many people meditating on the current situation, on one side or another. We’ve been so bombarded with information that at times it’s hard to keep it all straight. Everyone is posting to raise awareness, or to make rallying cries for support, or musing on how fortunate they are. I don’t want to spend this post doing any of that, but I also didn’t want to seem like I was making light of the very real and very serious situation that we’re in. So here we go: - I’m complaining about having to switch to online instruction, sure, but I’m aware that it could be much worse. At least I can transition to online, and my students have (mostly) been great. - I have friends and family who are in the high-risk group. I worry about them. - Many people in my life work in healthcare. I also worry about them, and am extremely grateful that they keep doing what they’re doing, even more so than usual (many of my college friends were pre-med or pre-nursing. It’s no picnic. English is so much easier). Okay, now that that’s out of the way... Thoreau has gotten a lot of flak over the years for Walden, and deservedly so. The book is a dreadful, self-indulgent slog, and every few years somebody new points out that Thoreau wasn’t as independent or isolated as he claimed to be. If you want a work celebrating the natural world, simplicity, and/or self-reliance, there’s a laundry list of better and more enjoyable reads to choose from. But the reason I bring him up is because it seems to relate to our current lifestyle, or at least to mine. We’re isolating, but we’re not totally isolated. Even though the only person I see on a daily basis anymore is my girlfriend, who lives with me, I am constantly texting, and calling, and video conferencing with the important people in my life. The fact that I can’t go out anywhere to act on these social impulses is surreal, and in those moments that I’m not interacting with someone via technology I find myself alone with nothing but my thoughts and my immediate surroundings, much as Thoreau was for his time in the woods. I’m not living simply, certainly not in the way that Thoreau intended when he started his “isolation,” but I am living more introspectively. As much as it feels like a man trying to prove that he’s better than everyone else because of his experiment, Walden also serves as a meditation on what happens when you’re alone with your thoughts, and the kinds of things you notice when you’re not swept up in everyday life. I can get behind the spirit of that idea, even if the execution leaves something to be desired. And that’s what I’ve been doing. Sure, I have grading to do and assignments to plan, and I spend a lot of time reading, or watching movies, or playing video games, but there are many moments in a day when I’m doing nothing. It’s not stagnation, and it’s not boredom. I just find myself sitting quietly for a moment, listening to the sounds on my semi-deserted street as I reflect on...whatever pops into my head. Sometimes I stare at my bookshelf, or the art on my walls, not because I’m looking for any sort of inspiration, but just because they’re there, and serving as convenient focal points. There’s something pleasant about it, and a weird kind of enjoyment in the knowledge that I don’t have to be anywhere, regardless of the reasons why. So yes, I think I’ve made the transition to quarantined life better than most. I don’t mind my thoughts, or being in the same space all the time. I realize that I’m fortunate in that regard--several of my more extroverted friends are going a bit stir-crazy right now. But if what the world needs from me is to stay indoors, in my pajamas, drinking tea and watching movies as I occasionally drift off in though, then by God I will do my duty. Maybe I’ll even squeeze some writing in there. Stay safe, friends. Don’t go out unless you have to. Wash your hands. Get some sleep. And, as Douglas Adams famously advised in large, friendly letters: DON’T PANIC. ~NG  This is another of what I like to call a demi-post. I did one a while back as an opportunity to get on my soapbox and talk about voting. Today I’m using one to revisit what I promised several weeks ago. So stow the pillory, for now at least. The ghost story is done...after a fashion. The arc is complete, the pieces are there, but I don’t think it’s quite finished yet. I’ll likely continue to tinker with it before I seek to formally publish it, but for those of you who want a spooky read, enjoy. It is November 2nd, and I’m proud to say I’ve managed to watch my 31 horror movies in 31 days for the second time since I started attempting this. I always try to watch as many new ones as possible, but I end up revisiting a few old favorites every year, and I always conclude the same way: on Halloween night, I watch Theater of Blood. There were a number of good new ones this year, including some indie films that I’d never heard of before watching them. I think overall this was the best year, ranking-wise. My top five are as follows:

Hope you had a Happy and Spooky Halloween, my friends! Until next year! ...with the spookiness, that is. I promise to post before then. -NG  I know I’ve been rather silent on, well, all fronts in recent months. There’s no point in making excuses; I have largely been idle with no real justification as to why. I’m putting my nose to the grindstone again, however. I’m working on a reread/revision of Morningstar with the long-term intent to republish; I’m fiddling again and again with the project I’ve been working on in the meantime, and I’ve even decided to return to what got me into the realm of fiction writing so many years ago: the short story. The realization that I wanted to tell stories came in fifth grade, when I received accolades for a short story that I wrote in response to a standardized test essay prompt. It was something along the lines of “if you could meet anyone in history, who would it be and why,” and I somehow decided that I needed to spin a yarn about traveling back in time to meet the infamous pirate Blackbeard, who I unwittingly cast as a misunderstood and sympathetic Robin Hood-type figure, rather than the bloodthirsty marauder that he actually was. I’d done it without a moment’s hesitation, so it came as quite a shock when I was showered with praise from people I had never heard of but was assured were very important to the school district. At the time I wasn’t under the impression that I had done anything particularly creative, unusual, or interesting. What I did understand, however, was that people liked what I had written, and that was an experience that I wanted to repeat. Over my grade school career I penned a couple of additional short tales, all with similar results. My dad reminds me every so often that he still has a copy of that Blackbeard story. I can’t decide if it’s something I’d like to read as an adult. But back to the present: I’ve been dabbling in short fiction again. It’s purely self-serving, of course; when I hit a block on one thing, I turn to another in the hopes that it will spark inspiration. I’ve long had ideas swimming around in my brain that I don’t think are viable enough for a full-blown book, so it seems only right to get them down. At least two of them deal with the spooky and the supernatural, so I’m hoping to have one of them done in time for Halloween. There you have it, readers. I’m promising a ghost story for Halloween. Hold me to it. Give no quarter if I fail to deliver. Pillory me and throw tomatoes. It’ll be what I deserve. On the subject of Halloween: longtime followers of mine know that, each October, I make an attempt to watch 31 horror movies in 31 days. In a perfect world, that amounts to one a day, which is entirely reasonable, but life is rarely entirely reasonable, and I’ve only ever managed to pull off the feat once in the five years I’ve attempted it. I’m on track thus far for this year; hopefully I can keep it up. I’ll have a debriefing once the month is over, and run down the list and highlight my favorites (I have favorites already, but there’s still nine days to go, so no sense jumping the gun). That’s all for now. If anyone knows of any underappreciated horror films for my endeavor, do let me know. -NG October’s barely begun, and it’s already shaping up to be a busy month.

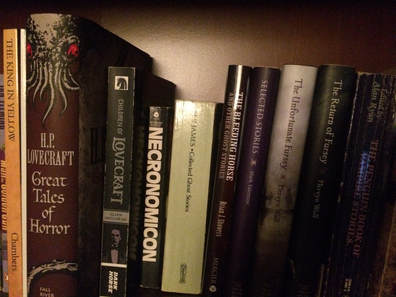

I’ve talked at length about my fondness for October before. In addition to the encroaching fall weather (however difficult that might be to imagine when it’s 70 and sunny, as it is now), the world turns its attention once more to the gloomy and macabre. With Christmas slowly devouring the calendar, I’m glad that people get into the Halloween mood the moment September ends. Maybe the Yuletide encroachment will stop with Thanksgiving. This particular Halloween is a momentous one; it marks the 200th anniversary of Frankenstein, and universities and libraries across the world are participating in “Frankenreads,” a marathon reading of Shelley’s novel on October 31st. One of my local libraries is participating, and I’ve signed up to join in the fun (how could I not, given the material?). As of yet I have no idea which section of the novel I’ll be reading, but from 12:50-1:00pm I’ll be contributing, and I’m very much looking forward to the experience. Several weeks prior to that, however, I’ll be talking about horror stories more generally. My alma mater has once again invited me back, and on October 18th I’ll be a guest speaker at Huntingdon’s October Art Walk, where I’ll be talking about scary stories and fear and what makes for good horror. Those of you that plan on attending, prepare yourselves for some fangirling over M. R. James, Robert W. Chambers, and H. P. Lovecraft. Other than these formal academic observations, my own less formalized celebrations are well underway. Two years ago, I published a list of “spooky reads” on Goodreads, and included a link to the horror curriculum I made for a friend back in college. I'll be pulling from both of those throughout the month to get myself in the mood. I’ve also begun my annual attempt to watch 31 horror films during the 31 days of October (it’s the 3rd and I’ve done three, so I’m right on track so far), and increasingly during the next few weeks I’ll break out my ever-growing Spotify playlist of Halloween-themed songs (link here; any suggestions obviously welcome). In short, I’m very much looking forward to my favorite month of the year. Feel free to offer any suggested reads, watches, or listens in the comments. I’m always looking for new additions to my repertoire. Happy Halloween! |

AuthorWriter, professor, occasional ruminator Archives

October 2018

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed