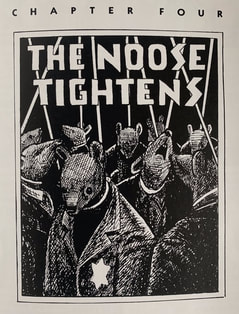

I’ve gotten on my soapbox about book banning before. I don’t often like to get on soapboxes, but as a writer, English professor, librarian, and all-around book nerd, it’s something that I am intensely passionate about. My students have to endure this every year when I force them to observe Banned Book Week. Fortunately, they’re largely receptive to the idea once they learn about it. They protest when they hear the books that are targeted, and write passionate defenses explaining why everyone should read their favorites. Sadly, this is not the case for everyone. Over the past several months, there has been a disturbing uptick in the removal or banning of books from school libraries and curriculum, not to mention determined efforts to silence the teaching of certain subjects. I won’t go into exhaustive detail of these various incidents here; NPR recently did an extensive report on the subject (well worth a read). Most of the book bans are along the lines that the American Library Association has extensively reported on for years. The most high-profile of these, however, came a little more than a week ago, when the school board of McMinn County, Tennessee voted to remove Maus from the eighth grade curriculum. The ruling has already garnered backlash and international attention, including a response from the author himself. If you’re not already familiar with the work (either prior to or as a result of this to-do), Maus is a graphic novel written and illustrated by Art Spiegelman. Published serially from 1980-1991, two collected volumes were released shortly thereafter. In addition to overwhelmingly positive responses from readers, Spiegelman’s work won numerous awards, including the Eisner for best graphic album and the Pulitzer Special Prize for letters. To date, it is the only graphic novel to have won a Pulitzer. Furthermore, Maus is considered by many critics to be among the most influential graphic novels of all time and–along with works like Watchmen, The Dark Knight Returns, and The Killing Joke–a major reason that graphic fiction is no longer considered a medium just for kids, and why in the decades since there has been a surge of critically acclaimed graphic fiction that goes far beyond the stereotypical superhero story. Of course, just because a work of literature is celebrated doesn’t mean that it’s appropriate for children. Up until this ban was implemented, the book was part of the district’s eighth-grade curriculum, and the board felt that the book was not appropriate for the age group. The school board provided their reasons for implementing this ban, citing “rough, objectionable language” (the minutes mention a total count of eight curse words) and the depiction of a nude woman. One board member additionally mentioned scenes of violence, including execution and suicide. On the surface, that certainly sounds extreme, but these objections seem less reasonable when considered in context. See, Maus is about the Holocaust. Specifically, it is the true story of Spiegelman’s father Vladek, a Holocaust survivor, in the years before, during, and after World War II. Spiegelman himself is a character in the frame story, which is set in 1978 as he slowly convinces his father to tell his tale. The art is simple and cartoonish, entirely in black and white, and uses anthropomorphic animals to represent the various groups involved in the war. Spiegelman, his father, and the other Jews (whether European or American) are mice, the Nazis are cats, Americans are dogs, Poles are pigs, French are frogs (excluding Spiegelman’s wife, a French woman who converted to Judaism for marriage), Swedes are reindeer, British are fish, and Gypsies are moths. Despite this, the story is powerful and personal, perhaps more so because the reader is not expecting it from the presentation. Despite Vladek’s flaws (which Spiegelman does not shy away from), the reader connects with and deeply empathizes with him and the other mice as they are persecuted, imprisoned, and yes, even executed. Children learn about the Holocaust in school. It’s not uncommon for them to read Anne Frank’s diary in middle school (I did, in 7th grade, and three years later Night was part of the curriculum). Lessons focus on the events of World War II and, while the gorier details are usually omitted in the younger grades, the Holocaust is mentioned. It has to be. And especially because there are fewer and fewer survivors and witnesses to the Second World War left each year, it is becoming increasingly rare for younger generations to feel a personal connection to those events. My grandfather (a WWII paratrooper) never talked about his experiences with me, but I was acutely aware that he was there, that these horrors were in living memory, and that made it feel more real and alive than other events that I learned about in history class. We can teach children about history all we want; we can drill dates and names and statistics into their heads and make them memorize them, but it’s difficult to connect with numbers and figures. You can tell someone that an estimated six million Jews died in the Holocaust, not to mention the millions of non-Jews, but the sad reality is that a figure like that is difficult to wrap one’s head around. We can understand in the abstract that people were arrested, imprisoned, tortured, and murdered in massive quantities, but it would break us to connect genuinely with the suffering of each individual victim. It is for this reason that literature about this time is so important. The first-person narration of someone who lived it, who watched as their rights were ripped away from them and they were treated like vermin, touches us in a way that no amount of facts and figures can. Even in Maus, Vladek protests that his son is including details that have “nothing to do with Hitler, with the Holocaust.” Art responds that he’s including them because “it makes everything more real–more human.” I’ve long forgotten most of the details that I was taught in history class about World War II, but the images that I read in Elie Weisel’s Night in my tenth grade English class are burned into my brain. Those 120 pages and the pain, longing, and despair they inspired will be with me for the rest of my life, and I’m glad of that. The Holocaust was one of the darkest moments in human history. But we can’t look away from that darkness. There’s a reason so many Holocaust memorial efforts (including the one from the German government) use the slogan of “Never Forget.” Looking at the brutality, understanding why it happened and who it happened to, helps us not only understand it, but to learn from it and ensure that it never happens again. Naturally, all of this is reasonable in principle, but the question remains: how much of this do we expose children to? This is the question that plagues so many of these controversies, and is often at the heart of challenges made to the ALA in the first place. Many of the challenges made to books are done so on the basis of protecting children from inappropriate content: violence, drug use, sexual content, racism, etc. Those who call for bans claim that they’re doing so for the greater good, that children are too impressionable to be seeing or reading about these things. The question, then, is when can they learn about these topics? Is it going to be upsetting for some students to see and read about the events of the Holocaust? Of course it is. The events are upsetting. But they are going to have to learn about these events sooner or later, and literature is the best avenue for teaching them. In her essay on trigger warnings, English educator Siobhan Crowley argues that excluding material from the curriculum because it contains potentially upsetting content amounts to “criminal neglect.” The list of literary works that engage with upsetting or problematic content is extensive, often because authors deliberately set out to discuss exactly these issues. “Great literature is great,” Crowley declares, “because it tackles these painful topics.” Literature offers us an avenue into these events and a chance to connect and identify with people who experienced some of the most impactful moments of history, and the teaching of literature provides young people with a space to engage with and discuss the issues connected to those events. Coddling students does them no favors. They will become aware of these issues regardless. Classrooms should be safe havens; these topics shouldn’t be drilled into their heads without context and discussion, and the perception that this is what happens is woefully misguided. No teacher would simply force their students to read Maus and declare “there you go. Holocaust bad.” That’s not teaching. Teaching is discussing and analyzing and providing students an opportunity to voice their thoughts and reactions. And yes, that includes moments that might be confusing or scary, but a classroom is the place to tackle those moments safely. The detriment that comes from depriving students of a mature and thoughtful discussion of these “upsetting” materials becomes even more apparent when you consider that these bans simply don’t work. Students are still reading the content. If anything, banning a book only makes it more attractive. Sales of Maus are up more than 700% in the wake of the McMinn County ban, and vendors are offering to send the book to impacted students for free. Students will access these materials regardless. Even if you disagree with the content, you should acknowledge the value in allowing young people to discuss the content openly and without fear of reprisal. It’s how we ensure that they truly understand the material, and learn the lessons that literature is intended to teach.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorWriter, professor, occasional ruminator Archives

October 2018

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed